Two aid workers were kidnapped in Yemen in June 2022 while working for Doctors without Borders; in October 2022 an aid worker in Ethiopia was killed while working for the International Rescue Committee, and another was killed in an ambush while working for Solidarités International in Mozambique in November of the same year. While once these headlines may have stood out as jarring and exceptional events, incidents of this nature have become increasingly commonplace.

It is a disturbing premise that aid workers entering a region in the hopes of relieving suffering might become the victims of violent attacks. Understood as altruistic good Samaritans, foreign aid workers have long been viewed as illegitimate targets in the context of war and conflict. They have been protected by the moral assumption that these bringers of aid should not become targets of assault. Sadly, however, this is exactly what seems to be happening.

Violence Against Aid Workers is on the Rise

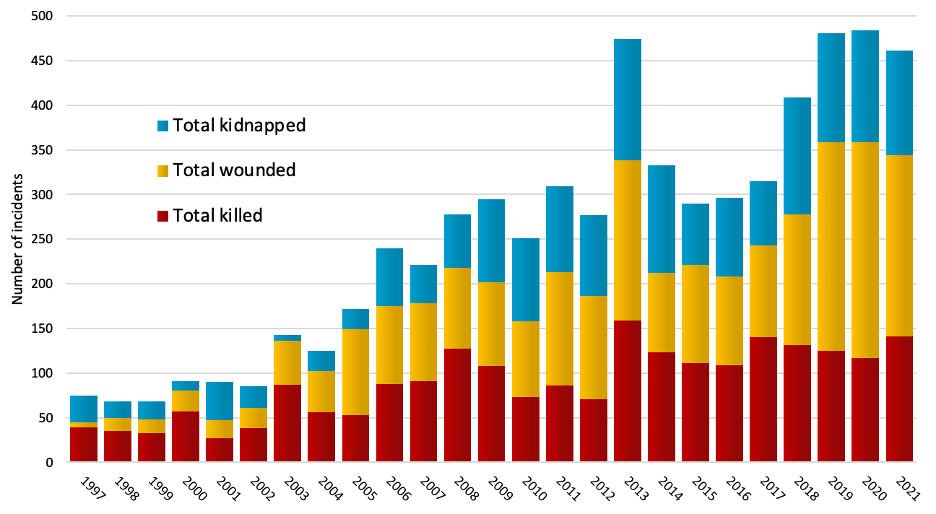

According to the Aid Worker Security Database, in 2021, 461 aid workers were involved in some 268 violent incidents, for a total of 117 people kidnapped, 203 injured and 141 killed. The year before, 484 people were involved in such incidents, resulting in the deaths of 117 aid workers. While these numbers vary from year to year, the global community has witnessed a fairly consistent rise in these events over the last few decades, as we can see from the figure below.

Incidents of Aid Worker Violence (1997-2021)

Source: Aid Worker Security Database https://aidworkersecurity.org/

But what is causing this surge in violence against aid workers?

Often, research on aid worker violence points to growing global insecurity and the looming threats present in areas most in need of aid. This line of reasoning may highlight the degradation of security in areas where aid workers are already based or may suggest that aid workers are increasingly going to areas that are more at risks of attacks.

There is very limited research that explores violence committed against aid workers; perhaps the best exploration of this phenomenon is captured in Larissa Fast’s 2014 book, Aid in Danger: The Perils and Promise of Humanitarianism. In this book, Fast challenges the dominant perspective that holds aid workers as blameless in violent incidents. While not going so far as to blame the victim, she dismantles the sacrosanctity of aid workers, pointing to opportunity-related causes for the surge in aid worker violence.

Fast exposes the disparity between well-compensated aid workers and the people they are meant to help, which can ultimately undermine local relationship-building efforts. Fast also points out that an influx of foreign aid can represent a unique opportunity for those eking out a living in poor regions of the world. As such, we may find heightened criminal activities in areas ripe with foreign aid-funded projects; ultimately creating friction points that spark violence. Demet Yalcin Mousseau’s 2020 article supports this hypothesis, providing empirical evidence that reveals a strong relationship between foreign aid and ethnic war.

The Securitization of Foreign Aid

Focusing instead on a geo-political trend, the last few decades have also seen a securitization of the foreign aid agenda. Securitized aid refers to aid that is employed as a tool to improve security within “developing” countries and, by extension, promote greater global security to the benefits of both “developing” and “developed” countries. Securitized aid not only applies to aid going to insecure or conflict-affected areas of the world but also to that targeting security-related aims, e.g. civilian peace-building, security system reform and post-conflict reconstruction.

In an ongoing research initiative, we have been digging into whether the increasing amount of securitized aid is related to an increase in violence committed against aid workers. For this project, we used data from the OECD DAC and the Aid Worker Security Database and employed cross-national multivariate statistical analysis to explore the relationship between these two variables for the period 1997 to 2021. Our models look specifically at securitized aid flows coming from all donor countries and the frequency of aid worker kidnappings, injuries, and killings.

Controlling for such variables as ongoing conflict, poverty, and governance, our preliminary findings show a strong correlation between the amount of securitized aid coming into a country and increased violence against aid workers.

Securitized aid is aid that inherently blurs the line between military, humanitarian, and development activities. This approach to foreign aid may generate problematic local perceptions; individuals in the community may wonder if the humanitarian workers they encounter are neutral assistance providers or para-military agents. This confusion runs the risk of directing undue negative attention toward these workers.

We are thus left with a paradox; aid that is intended to improve security may, in fact, be degrading it for those most intimately involved in its implementation: aid workers.

Where do We Go from Here?

Understanding that a relationship exists between securitized foreign aid and violence towards aid workers draws into question the appropriateness of securitized aid. As there is no definitive evidence suggesting that securitized aid has in fact improved global security; is it worth continuing with this type of foreign aid if it puts aid workers at risk?

The securitization of aid is one of the determinants of violence committed against aid workers, but it is not the only one. Individual and organizational concerns like those raised by Fast represent critical considerations in understanding violence towards aid workers. Greater attention and empirical analysis related to these concerns would help deepen our understanding of aid worker violence.

Should we wish to see the troubling trend of aid worker violence reversed, we need a careful and pragmatic investigation into how the engines of foreign aid have evolved. We need to look more closely at the varying forms of securitized aid and understand their relation to aid worker violence. We must also suppress the tendency to absolve aid workers from any blame associated with their work, and look at their role objectively, with the goal of improving security for all.

1 comment