Myths are defined as narratives deeply embedded in the fabric of human societies across time and cultural groups. They range from the Ancient Greek myth of Perseus and Medusa, to the Western belief that we must consume eight glasses of water a day. While myths may strengthen cultural identity and teach valuable lessons, they also hold the power to promote stereotypes and injustices. How have myths been used to distort and downplay –if not erase- the role of Indigenous people around the world?

The experiences of the Mi’kmaq in Ktaqmkuk (Newfoundland, Canada) and the Moriori in Rēkohu (Chatman Islands, New Zealand) are revealing here. While the two islands may seem worlds apart, separated by over 16,200 km, they are both former colonies of the British Empire. As part of this shared colonial history, Indigenous Peoples in Newfoundland and Labrador (NL) and New Zealand have faced –and despite residential schools closing in 1980 in Newfoundland and Native Schools closing in 1969 in New Zealand, continue to face— similar threats to their cultural security via the promotion of harmful myths.

NL’s Mi’kmaw Mercenary Myth

The Mi’kmaw Mercenary Myth in NL refers to the idea that the Mi’kmaq, an Algonquin First Nations group ancestral to what is now Atlantic Canada and the northeastern United States, are not Indigenous to Newfoundland. Taught in provincial history classes up until the 1990s, this colonial teaching has shaped popular culture in the province, with many believing that the Mi’kmaq were in fact brought to the island by French settlers in order to kill the Beothuk, another Indigenous group.

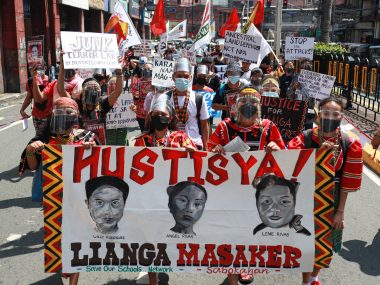

Thanks to Mi’kmaq oral history and anthropological evidence, we now know that this myth is not supported by historical records or evidence, but the damage to the Mi’kmaq’s cultural security is already done. At the 2023 Canadian Archaeological Association’s Annual Meeting, some conference participants did not believe Mi’kmaq even lived in Newfoundland today, even though my colleague, a Newfoundland Mi’kmaw archaeologist, was present at the conference. In fact, statistics indicate that there are 27,524 Mi’kmaq in Newfoundland today (3,060 associated with Miawpukek First Nation and 24,464 associated with Qalipu First Nation).

This colonial myth also helps shift responsibility for the genocide of the Beothuk –an Algonquin group whose traditional territory is the island of Newfoundland and who are thought to have “died out” in 1829—, from the Newfoundland colonial government to the Mi’kmaq. The belief that the Mi’kmaq only had hostile relations with the Beothuk has also been proven false, as Mi’kmaw Elders and community members tell of friendly relationships between the Mi’kmaq and Beothuk in Newfoundland, evident in the blended Mi’kmaq-Beothuk families recorded by famous American anthropologist Frank Speck, Chief Joe of Miawpukek First Nation, and in recent DNA studies.

New Zealand’s Moriori Myth

Myths have also negatively affected the cultural security of other Indigenous populations around the world. Taught in New Zealand schools and even published in textbooks in 1916 and 1946, the Moriori Myth claimed that the Moriori, a Polynesian Indigenous group from Rēkohu (the Chatham Islands) in New Zealand, was a primitive society unable to survive competition with the Māori, another Polynesian Indigenous group, who were thought to be a superior, more warlike society. This myth suggested that the Māori entirely wiped out the Moriori during the Māori-Moriori conflict in the 1800s.

European settlers then used this myth to justify the colonization of New Zealand, claiming that Europeans displacing Indigenous Peoples was just a process of cultural replacement with a more advanced, superior group—i.e. a natural progression for human societies and the same situation as when the Māori “wiped out” the Moriori. Equally important, this myth removed the Moriori from New Zealand’s history, effectively undercutting their Indigenous Title—the inherent right Indigenous Peoples have to their territories based on temporal priority (i.e., that they were here before settlers). While it is true that the Moriori did experience genocidal conflict with the Māori in 1835, the Moriori people did survive and continue to live in New Zealand today, with the Hokotehi Moriori Trust claiming over 2,000 registered members and estimating over 6,000 people globally with Moriori ancestry.

Shared Struggles: Progress and Moving Forward

Myths can influence society in two ways: they can impact essential teachings and solidify cultural belonging; but they can also be used to influence national identities and histories—whether they are true or not. Myths used to support inaccurate narratives may have wide-ranging implications, from promoting stereotypes, distorting history, and downplaying the role of some actors —as seen in the Mi’kmaw Mercenary Myth and Moriori Myth.

However, thanks to the work of many Indigenous activists and settler allies, these myths of erasure are slowly being corrected. For the Ktaqmkuk Mi’kmaq, Miawpukek First Nation was first recognized in 1987, while Qalipu First Nation was recognized in 2011, both under the Indian Act. Most recently, the Moriori achieved recognition under the Moriori Claims Settlement Act in 2021. Though these Indigenous groups have been recognized by their respective settler governments, much work remains to be done to help undo the erasure caused by these myths, including more research into Mi’kmaw archaeology on the island of Newfoundland, the repatriation of Mi’kmaq and Moriori cultural belongings to their traditional territories, better representation in museums, and more representative public education curriculums. Understanding how myths shape cultural safety and security can help us foster a more resilient, inclusive, and just society.